Ten years in WTO have given valuable lessons

|

Vietnam’s admission into the World Trade Organization (WTO) decade ago was a natural progression of the country’s international economic integration after it had shifted to a market-based economy model. This was an important cornerstone, marking Vietnam’s deepened engagement with international economic institutions; prior to accession, Vietnam had already partnered with the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, and the Asian Development Bank.

Evolving to match contemporary requirements

The WTO accession meant Vietnam was required to adhere to international rules on investment and trade liberalisation, while national economic institutions needed to be amended and improved to match international principles.

Also, the country had to gradually open the door of the products and services market pursuant to its bilateral and multilateral agreements with other countries, and accept decisions of international arbitrators in dispute cases.

Vietnam applied to join WTO back in 1996. During the period from 1997 to 2001, government authorised agencies had to answer more than 1,500 questions from WTO member countries about the country’s legal system, and actual state of development.

From 2002 to 2007, Vietnam entered into multiple bilateral and multilateral negotiations with WTO member countries and the organisation itself. In the meantime, the country made constant efforts to improve its regulatory system to become eligible for WTO accession.

After joining WTO, the country’s legal system was further improved to make good on its WTO commitments. These commitments had to follow specific roadmaps for each particular economic sector.

Vietnam’s efforts in revising and improving the legal system around WTO accession walked a line between the country’s innovation and conservatism, between trade liberalisation and trade protectionism, between respecting companies’ rights to do business and maintaining the old ‘ask and give’ mechanism. At the heart of these efforts was an ideological dispute between a pro-business model of governance and efforts to maintain the centrally-planned, bureaucratic state.

This battle would eventually result in concrete results, particularly the 2014-amended Law on Enterprises and the 2014-amended Law on Investment. The government also started requiring businesses to apply the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) standards in taxation and ASEAN-4 countries’ standards in customs fields.

But not everyone was on board with this direction. Some tried to dull this pro-business progress through imposing conditions and procedures that hampered business operations to reap their own benefits. This is why efforts were made to retain regulations on conditional business fields, requiring sub-licence provisions.

In addition to those resisting the changes, law enforcement bottlenecked around the enforcement of business practices.

The preparation and implementation of WTO commitments soon became a task of foremost importance to the country. This was demonstrated in the Central Party Committee Resolution and government’s Action Programme on the issue.

Once WTO accession was gained, these processes were carried out simultaneously across ministries, sectors, and localities. Organisations specific to WTO were founded to provide consultation to businesses.

Many documents, including the WTO Handbook, were published. Never before had the country’s business climate shown so much life as in the months after Vietnam’s accession to WTO. These diligent preparations aroused commercial confidence in Vietnam’s future development.

And now, as Vietnam engages in a raft of new-generation free trade agreements and the ASEAN Economic Community, the lessons of WTO accession are more important than ever.

|

| When Vietnam acceded to the World Trade Organization 10 years ago, it was the real start of the country’s international integration. Over 10 years of membership, WTO obligations have paved the way for institutional reform, setting the stage for the FDI interest the country has reaped in the years since. |

Achievements in international trade and investment

The global economic recession took place in 2008, causing detrimental impacts to Vietnam’s economy through slowing down economic growth and igniting high inflation. The government concentrated resources on tackling the new situation; delaying the implementation of the Action Programme on the WTO for several years.

To review progress on the five-year anniversary of WTO accession, on August 14, 2012 the government convened a national conference to review the implementation of the Resolution and the Action Programme on WTO, seeking comments and issuing a government resolution on “Accelerating and improving efficiency of international economic integration during 2012-2015, with an orientation to 2020”.

Expanding international trade relations through increasing trade values and the restructuring of export type are positive effects of Vietnam’s accession to WTO.

Accordingly, the proportion of natural resources and raw materials in the export structure has been reduced alongside an increased percentage of manufactured products.

Among manufactured products, the rate of high-tech items rose the sharpest. The rates of raw and manufactured items in the export structure were 44.6 and 55.4 per cent in 2007, respectively. In 2015, these figures stood at 23.8 and 76.2 per cent.

Before 2012, textiles, garments, and footwear were Vietnam’s major export items. In recent years, electronic items have superseded them in the export structure.

Domestic and foreign-invested businesses have made growing contributions to Vietnam’s international trade, with foreign-invested enterprises (FIEs) becoming more eminent players.

Local businesses contributed 42.8 per cent to the 2007 export value, whereas the remaining 57.2 per cent was produced by FIEs. Corresponding figures for 2015 were 29.5 and 71.5 per cent, respectively.

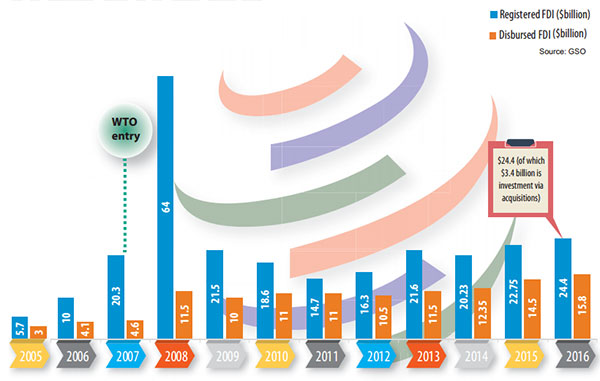

Vietnam’s foreign direct investment (FDI) attraction is the brightest point in the past decade. Total disbursed FDI volume was $8.03 billion in 2007, increasing to $11 billion in 2010 before reaching $14.5 billion in 2015 and $15.8 billion in 2016 – nearly doubling the level of 2007.

This is an important indicator reflecting Vietnam’s attraction towards FDI capital flow compared with other regional peers.

The quality of FDI has also improved markedly, as scores of global tech players such as Intel, Microsoft, Samsung, LG, Nokia and Canon have all deployed large-scale projects in Vietnam, making significant contributions to restructuring Vietnam’s economy following a new growth model. The gap between committed and disbursed FDI volumes narrowed remarkably.

Registered FDI volumes reveal investors’ commitment to project implementation, and best demonstrate FDI development trends. However, after the government decentralised the power onto localities and management authorities of industrial parks and economic zones, there were cases of several management agencies paying special attention to capital-intensive projects while neglecting investor quality.

Consequently, myriad licensed projects were found lying idle across the country.

Things saw a turnaround in recent years. Localities throughout the country reportedly took back investment certificates for hundreds of idle projects last year.

Foreign-invested projects valued in the million and billions of US dollars in capital began to commission in shorter windows of time after getting investment certificates – in many cases, in less than one year. This has helped shorten the gap between committed and disbursed FDI amounts.

In short, during the 10 years since WTO accession, international trade and foreign investment have been two of the biggest driving forces propelling national economic growth. They have done this through increased labour efficiency, sharpened competitiveness of local products and businesses, and an improved image of the country in the world.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- US firms deepen energy engagement with Vietnam (February 05, 2026 | 17:23)

- Vietnam records solid FDI performance in January (February 05, 2026 | 17:11)

- Site clearance work launched for Dung Quat refinery upgrade (February 04, 2026 | 18:06)

- Masan High-Tech Materials reports profit: a view from Nui Phao mine (February 04, 2026 | 16:13)

- Hermes joins Long Thanh cargo terminal development (February 04, 2026 | 15:59)

- SCG enhances production and distribution in Vietnam (February 04, 2026 | 08:00)

- UNIVACCO strengthens Asia expansion with Vietnam facility (February 03, 2026 | 08:00)

- Cai Mep Ha Port project wins approval with $1.95bn investment (February 02, 2026 | 16:17)

- Repositioning Vietnam in Asia’s manufacturing race (February 02, 2026 | 16:00)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version