Automation spelling doom for manufacturing hotspots?

|

| 70 per cent of Vietnamese jobs are at risk of automation (Source: Huffingtonpost) |

The developed world has made leaps and bounds by industrialisation and building out low-skill, labour-intensive manufacturing lines to stand where they are now.

Many lower-income countries jumping on the bandwagon later on have achieved spectacular economic growth by shifting to low-end manufacturing that is exceptionally labour-intensive, like textile and garment and footwear production where workers coming from low-productivity smallholder agriculture could be easily trained to task.

Indeed, as reported by The Guardian, industrialisation has driven an “unprecedented convergence between rich and poor country wealth levels,” as by the early 2000s 83 developing countries were growing at twice the rate of OECD members.

However, simply following the footsteps of developed countries is not viable as the gains of industrialisation and low-skill manufacturing are being eroded by the emergence of automation.

Harvard economist Dani Rodrik, as cited by The Guardian, said industrialisation is rapidly losing its magic: most developed countries have gotten richer than the countries that follow after them and are now turning away from manufacturing.

By Rodrik’s calculations, industrialisation peaked in western European countries, such as Britain, Sweden, and Italy at income levels of around $14,000 (1990 levels), while it peaked in India and Sub-Saharan African countries at $700 (1990 levels). In fact, Latin America and Africa, the latest joiners of industrialisation, are already showing signs of deindustrialisation.

The biggest challenge to manufacturing is automation and the fast developing computing capacity. As computers evolve, machines can learn more and more low-skill tasks and take over with more precision and speed. Bear in mind, it is mostly low-skilled jobs that are in danger, while medium and high-skilled positions are relatively safe.

A major advantage offered by countries delving into industrialisation is the abundance of cheap, unskilled labour force. If this is undercut by automation, there will be little left going for manufacturing countries and large-scale international companies may elect to take production closer to the end users.

Adidas, as reported by The Economist, has already started building an automated factory in its home country Germany. Apart from the fact that this novel production facility will use a range of advanced techniques, such as 3D printing, to produce customised trainers and sports shoes for order, it is a definitive step away from favoured offshore production countries like China, Indonesia, and Vietnam.

Vietnam, China, and India are somewhat luckier as they ran in the second wave of industrialists and have attained middle income status by it. Slower economies hoping to take the same path ended less fortunate.

However, automation is becoming an increasing concern for all the countries that make up the manufacturing backbone of global industrial production. As reported by Bloomberg, installing robots along production lines is threatening to dent wages in China and impact the world at large.

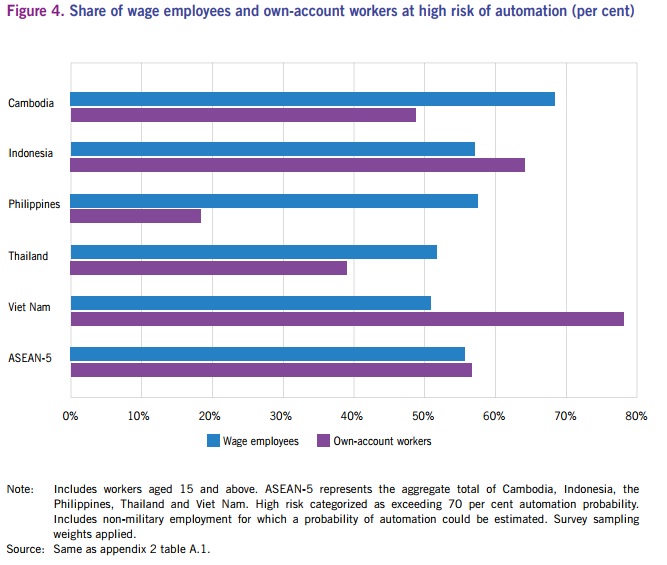

The International Labour Organization in the publication of “ASEAN in Transformation: the Future of Jobs at Risk of Automation” has reported that an alarming number of enterprises in Camdobia, Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam (named the ASEAN 5 by the report) are at high-risk of automation in the next couple of decades. 56 per cent of all employment, nearly three out of five jobs, have a high risk of automation in the five countries.

In fact, the risk is the worst in Vietnam, as about 70 per cent of jobs are in the high-probability zone of being replaced by machinery. Additionally, another 18 per cent of jobs has a medium risk, and only 12 per cent of all employment carries low risk of automation.

According to the ILO report, the share of low-skilled elementary occupations in total employment is the highest in Vietnam, with two out five jobs belonging to this category. Thus, the overall probability of computerisation is also the most pronounced.

|

| Self-employed Vietnamese workers are at a very high risk of losing their jobs to automation (Source: ILO) |

Another important data point is that self-employed workers (termed own-account in the report) are only slightly more at risk of automation than wage employees (57 per cent), belying significant disparities among the countries: while only 20 per cent of self-employed workers are in the high-risk zone in the Philippines, this ratio is about 65 per cent for Indonesia, and 78 per cent for Vietnam.

In the ASEAN 5, several common occupations account for a sizeable share of employment and are highly vulnerable to automation. According to the ILO report, about 27 million subsistence farmers and low-skill crop farm labourers across the five countries face a high risk.

In Vietnam, notable high-risk occupations include shop sales assistants (2.1 million), garden labourers (one million) and sewing machine operators (770,000). It is noteworthy, that while garment production was mentioned for Cambodia, it has not been so for Vietnam, probably because of the country’s more diverse economic activities.

For the ASEAN 5, key industries with high risk of automation include hotels and restaurants (80.7 per cent), wholesale and retail trade (77.5 per cent), construction (70.8 per cent), and manufacturing (61.6 per cent).

In Vietnam, the risk sectors are as follows: hotels and restaurants (93 per cent), wholesale and retail trade–repair of motor vehicles and motorcycles (84.1 per cent), agriculture, forestry, and fishery (83.3 per cent), and manufacturing (74.4 per cent).

Regardless of numbers, the garment and textile manufacturing industry is one of the most vulnerable to automation. Within the ASEAN 5, three out of ten wage manufacturing employees are working in this sector.

In Vietnam, this figure is two in five. A characteristically low-skill and labour-intensive production sector, this industry has become quite favoured in Vietnam and has been a great pillar of the Cambodian economy.

Similarly, food and beverage production is another area highly affected by automation. This area is responsible for 15 per cent of all manufacturing salaried jobs in Vietnam.

The prospects drawn up by these numbers are quite bleak. But what will come about in the future? How will the Vietnamese economy be affected?

Vietnam’s future on the scale

To evaluate the impact of automation, two things need to be considered. Is Vietnam, or indeed any developing country, blindly rushing along in a prescribed direction or is taking initiative to steer development by the principles of sustainability. The other issue is whether Vietnam’s position in the global economy and what the economy has to offer for internationals is enough to counteract the advantages of moving production back to the developed world.

On the first question, it can be said with relative certainty that Vietnam does not blindly follow a 50-60-year-old development plan, but is going into serious efforts to attract higher value-added production and top-of-the-line technology to its manufacturing activities.

In addition, the country is delving into relatively diverse fields to ensure it will always stay on top: apart from manufacturing, Vietnam is an increasing highlight on the world tourism and hotels map, and the country’s newest education initiatives are promising to raise the next generation of globally employable engineers.

Since the beginning of the year to date, a veritable host of developments surfaced in the media promising better access to international-standard education domestically or overseas.

In June, Hanoi authorities and Singapore’s flagship educational institute KinderWorld Education Group signed a Memorandum of Understanding for a $100-million package of three educational institutions (Singapore International School, Pegasus Smart Uni-City, and Outward Bound Vietnam & Eco-tourism).

In August, Centre for Finance, Technology and Entrepreneurship (CTFE) has extended its education initiative to the greater ASEAN region, including Vietnam, with the purpose of training finance 2.0-compatible professionals.

Similarly, four universities in Vietnam are now accredited for meeting international standards by the French High Council for Evaluation of Research and Higher Education. Apax Holdings and Franklin Virtual Schools/Franklin Learning Centres have teamed up to provide US and global-standard education programmes to pre-university students right in Vietnam.

The city of Danang, parallel to Vietnam’s most major cities, is stepping up training in the IT and the communications sector to combat a serious shortfall in manpower. Talks of amending the curriculum to fit modern times and extending courses to increase the output of highly-trained engineers is a constant topic on the agenda. However, even all these initiatives might be insufficient to cover the country’s growing needs.

A report from VietnamWorks released in 2015 showed that Vietnam will need 1.2 million IT workers by 2020. However, if the number of IT professionals grows at the already high rate of 8 per cent, the country will lack about half a million workers.

The finance and banking sector has also been gathering speed, attracting numerous international names to seize its unexploited potential, especially at the life and non-life insurance segments.

The second question essentially comes down to a weigh-in of benefits. By moving production closer to the developed world, internationals can cut down on shipping and logistics expenses for their wealthiest and highest-spending customers.

On the other hand, Vietnam has been making leaps and bounds in its international integration efforts, signing a host of FTAs and economic accords. Through this, Vietnam will have tariff-free access to a significant portion of this half of the globe, as well as the European Union, and several other parts of the world.

The question for each producer is whether it is worth cutting down on logistics expenses and stay closer to developed markets or whether maintaining production presence in such a well-connected up-and-coming hotspot is more profitable.

What the stars mean:

★ Poor ★ ★ Promising ★★★ Good ★★★★ Very good ★★★★★ Exceptional

Latest News

More News

- Site clearance work launched for Dung Quat refinery upgrade (February 04, 2026 | 18:06)

- Masan High-Tech Materials reports profit: a view from Nui Phao mine (February 04, 2026 | 16:13)

- Hermes joins Long Thanh cargo terminal development (February 04, 2026 | 15:59)

- SCG enhances production and distribution in Vietnam (February 04, 2026 | 08:00)

- UNIVACCO strengthens Asia expansion with Vietnam facility (February 03, 2026 | 08:00)

- Cai Mep Ha Port project wins approval with $1.95bn investment (February 02, 2026 | 16:17)

- Repositioning Vietnam in Asia’s manufacturing race (February 02, 2026 | 16:00)

- Manufacturing growth remains solid in early 2026 (February 02, 2026 | 15:28)

- Navigating venture capital trends across the continent (February 02, 2026 | 14:00)

- Motivations to achieve high growth (February 02, 2026 | 11:00)

Mobile Version

Mobile Version